Wednesday, December 28, 2016

The Auteurs #62: Sam Peckinpah

Among one of the most polarizing figures in American cinema to emerge in the post-war era, Sam Peckinpah was an extremist in a lot of ways. While he’s made films that are considered standards of the western genre, he’s also managed to cause a lot of controversy in his graphic depiction of violence where he is often nicknamed Bloody Sam. Yet, those who had seen and praised his work see a man that is definitely an outsider where he would often battle studios to do what he wants while making films that talk about those who don’t fit in with the modern world or wanting to play by the rules. More than thirty years since his passing, Peckinpah remains a controversial figure by some yet others see him as one of the greats who was unwilling to compromise no matter how much the world was against him.

Born David Samuel Peckinpah on February 21, 1925 in Fresno, California to David Edward Peckinpah and Fern Louise Church. Fern’s father Denver S. Church was a superior court judge as well as a cattle rancher and a Congressman for the Fresno country district in California. The young Sam grew up in unique surroundings as he enjoyed time in his grandfather’s ranch learning the ways of cattle branding and other activities while also enjoying the emergence of westerns that were being made on film. It was a life that Peckinpah liked as it was sharp contrast to the surroundings of towns and the city where Peckinpah had trouble fitting in. While he able to play junior varsity for his local football team, he was eventually kicked out often due to fighting with other students causing his parents to enroll him at San Rafael Military Academy in his senior year. In 1943, Peckinpah enlisted to join the marines where would eventually serve World War II on the Pacific campaign.

Peckinpah would later attend the Fresno campus of California State University following his discharge as he would meet his first wife Marie Selland whom he married in 1947. While studying history, Peckinpah became interested in the world of drama as well as the idea of directing plays. With the sudden emergence of television, Peckinpah would work for a local TV station as a stagehand after completing his tenure in college where he hoped it would lead him to get experience in the world of film. Instead, Peckinpah found himself combative over what to do to play by the rules as he would fight with bosses. In 1953, Peckinpah’s life would change where he was given a job working as a dialogue coach on the set of Don Siegel’s noir crime film Riot on Cell Block 11 where he found a mentor in Siegel. Siegel would have Peckinpah work as a dialogue coach and eventually do re-writes on other projects as he would guide the young man to find his own voice.

The TV Years (1957-1962)

Siegel’s connection in the industry would give Peckinpah the chance to write for various TV shows that were emerging throughout the 1950s as many of them would be westerns. Shows such as Gunsmoke, The Rifleman, Have Gun-Will Travel, and Broken Arrow would allow Peckinpah the chance to hone his craft as a writer as he would also direct an episode of Broken Arrow in 1958 that would later get him directing gigs for shows such as Klondike and a sitcom in Mr. Adams and Eve as the latter starred Ida Lupino who would encourage Peckinpah to hone his craft as a filmmaker. His work in television would give him the chance to meet actors such as James Coburn and L.Q. Jones who would later become collaborators for some of Peckinpah’s films. In 1957, Peckinpah was asked to adapt Charles Neider’s novel The Authentic Death of Hendry Jones for actor Marlon Brando who was trying to create a western that was to be directed by Stanley Kubrick. Instead, problems on the project that eventually became One-Eyed Jacks would eventually helmed by Brando himself as he rejected Peckinpah’s script as little of the material ended up in the film.

In 1960, Peckinpah was given the chance to helm his own series for NBC entitled The Westerner as it would star Brian Keith. The show would be part of a series of TV westerns that NBC wanted as it would premiere in late September of 1960. While it was well-received by critics, the show didn’t do well in the ratings as it was cancelled at the end of the year though it did attract a cult following and gave Peckinpah a reputation as a reliable filmmaker who can create images that were expected within the western genre as well as explore themes of honor and loyalty.

The Deadly Companions

Following the cancellation of The Westener, Peckinpah was approached by Brian Keith about helming a film he is to star in that will co-star Maureen O’Hara with her brother Charles B. Fitzsimmons producing the film. Peckinpah agreed to meet with Fitzsimmons who would give Peckinpah the job as it would be a chance to helm a film for the very first time. With a cast that would include such noted Western character actors in Chill Wills and Strother Martin, the film be shot in Arizona with a very small budget as it would revolve an ex-army colonel whose attempt to stop robbers at a bank robbery has him accidentally killing a young boy. In a need to redeem himself, he would accompany the boy’s mother to bury the boy in a small town near treacherous land controlled by the Apache. Though Peckinpah was fascinated by the story as it had themes that he cherished, he would learn that he would have no control on what changes are made to the script as well as have a say in the editing.

Still, the job allowed him to give him the experience in helming a feature film as he enjoyed working with the actors including Wills who would become one of many actors Peckinpah would work with occasionally. After shooting and seeing what Fitzsimmons would do in the editing under his supervision, Peckinpah knew that if he was ever going to be offered the chance to make another feature film. It would be under his terms and under his control.The film made its premiere in June of 1961 where despite earning good reviews, the film didn’t go anywhere in the box office. Especially as another film Keith and O’Hara did earlier in The Parent Trap came out a week later where it was a major hit as Peckinpah’s film disappeared from theaters quickly. Yet, the film would later be discovered in the coming years as some saw it as one of Peckinpah’s overlooked gems.

Ride the High Country

After finishing up his work in television in shooting episodes for The Dick Powell Theater, Peckinpah met with producer Richard Lyons who liked Peckinpah’s TV work as he gave him a script by N.B. Jones Jr. about two aging gunslingers taking a job to transport gold from a remote mining town as they cope with the growing changes around them. Peckinpah said yes to the project as he would re-write the script with William Roberts with Jones’ input as it would be set in the early years of the 20th Century as it would play into Peckinpah’s theme with the emergence of the modern world and man’s reaction to these changes. Peckinpah would also infuse bits of his own personal life and background into the story. Especially as it gave the story more weight into the themes that Peckinpah wanted to explore as he cast Randolph Scott and Joel McCrea in the lead roles despite the fact that both men were no longer considered draws in the genre.

The cast would also include character actors such as L.Q. Jones, Warren Oates, and R.G. Armstrong were cast while Ron Starr was cast as a young cowboy aiding the old men and Mariette Hartley as woman who would join the men as she is to get married at the town they’re going to. Much of the film was shot around desert and mountain locations in California with some of it shot on studio sets as the film would mark the first in a series of collaborations with cinematographer Lucien Ballard. Ballard would give Peckinpah not just naturalistic images that played into the west but also a sense of scope that gave Peckinpah more of what to do visually. The production was quite smooth in comparison to some of the drawbacks Peckinpah endured with his first film as Peckinpah was ecstatic about making a film under his complete control. While the budget was quite small at over $800,000, Peckinpah was able to use his limitations to his advantage.

The film made its premiere in late June of 1962 where the film didn’t do well commercially when it was released by MGM as it disappeared for a while in the U.S. Later that year in Europe, the film premiered in film festivals where it was a major hit as some saw it a new and fresh take on the genre. In New York City, the film had become a cult hit as many of its critics lavished the film with a lot of praise as it made Time magazine’s top-ten list of the best films that year with Newsweek naming it the year’s best film. For Peckinpah, the critical support would prove to important as it helped raise Peckinpah’s profile.

Major Dundee

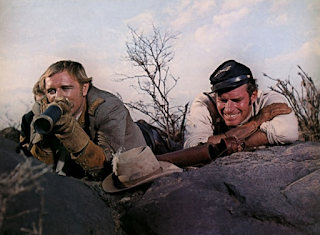

While Peckinpah was riding high on the critical success of Ride the High Country, the filmmaker had to wait for a new project to emerge where he found a script by Harry Julian Fink about a Union cavalry officer who teams up a mixed group of Army regulars, Confederate soldiers, and Indian scouts in dealing with Apache tribes wreaking havoc around towns in Texas and parts of Mexico. Peckinpah liked the script though he felt it needed work as he and acclaimed screenwriter Oscar Saul did a lot of re-writes where they focused on a man’s determination for glory much to the chagrin of those who are working under him. While working on the script which brought the attention of actor Charlton Heston who liked Ride the High Country, Peckinpah was asked to make the film with Heston in the titular role while the cast would include several of Peckinpah’s regulars in James Coburn, R.G. Armstrong, Warren Oates, and L.Q. Jones while it would also mark the first time Peckinpah would work with Slim Pickens and Ben Johnson.

For the role of the Confederate officer Captain Benjamin Tyree, British actor Richard Harris was cast as the film would be the first film Peckinpah made under a massive budget at around $3 million under the supervision of Columbia Pictures. When shooting began in 1964, it was made without a finished script as Peckinpah was trying to create something that was authentic with a large cast. One of the aspects that led to the film’s troubled production was that it would be shot in various locations in Mexico which was something the executives at Columbia didn’t like which caused the film to go over budget and be behind schedule. Adding to the chaos was Peckinpah’s consumption of alcohol which he had been known for as it would become something prominent for much of his career. The shoot was further troubled due to the action scenes as well as Peckinpah dealing with Heston, who was known for having a massive ego on set, though the two did have their moments where they had some fun.

By the time Peckinpah worked on the editing of the film with a trio of editors, Peckinpah’s original cut ran over 4 hours which would eventually turn into a more substantial cut running at a 156-minutes to Columbia. The executives weren’t happy as they wanted something shorter as well as put in a score by Daniele Amfitheatrof which Peckinpah hated. When the film was screened in March of 1965 with a running time of 136-minutes, it was panned by the critics which forced Columbia to take out thirteen minutes of the film for its theatrical release much to the protest of Peckinpah and producer Jerry Besler who was trying to help Peckinpah get his creative control. The film’s commercial failure was a major setback for Peckinpah as he was helming The Cincinnati Kid where he was seen in Hollywood as a renegade and was fired four days after filming as producers and executives didn’t like what he shot as he was replaced by Norman Jewison. In 2005, producer Jerry Besler was in charge in creating an expanded version of the film based on Peckinpah’s notes as it would include a new score by Christopher Caliendo. The restored 136-minute version of the film would receive a rousing reception from critics as even those who had been experts of Peckinpah’s work felt the film was a major improvement over the theatrical release.

Noon Wine

After the horrendous experience of Major Dundee and being fired from The Cincinnati Kid, Peckinpah’s career seemed to have been stalled until producer Daniel Melnick offered to help him out. While Peckinpah was considered a Hollywood outcast, Melnick gave Peckinpah the chance to helm a TV movie based on Katherine Anne Porter’s short novel about a farmer who invites an immigrant into his home to help out his ailing dairy farm where tragedy would later ruin them. Melnick gave Peckinpah complete control as Peckinpah would write the script himself as Porter would read it and approved it. With cinematographer Lucien Ballard on board after not being able to take part of the production of Major Dundee, the cast would also include Peckinpah regulars L.Q. Jones and Ben Johnson in small roles.

For the lead role of Royal Earle Thompson, Jason Robards was cast in his first collaboration with Peckinpah while Olivia de Haviland was cast as Thompson’s ailing wife. The production was an easier one as the project would also mark the very first time Peckinpah worked with music composer Jerry Fielding who would provide a mixture of orchestral and country-folk music that Peckinpah liked. The TV movie was released as part of ABC’s Stage 67 film series in late November of 1966 where it received excellent reviews from the critics. Though it wouldn’t be seen publicly for many years until it was released as part of an extra for a Blu-Ray release for one of Peckinpah’s later films in 2014. The film marked a turning point for Peckinpah as well as showing that he could do a lot more than make violent westerns by showing a sensitive side that would be unveiled in later films to come.

The Wild Bunch

Despite being seen as a pariah in Hollywood, there were some like Daniel Melnick that wanted to work with Peckinpah as did producers Kenneth Hyman and Phil Feldman of Warner Brothers-Seven Arts where they gave Peckinpah a script for an adventure film for him to helm. Yet, Peckinpah was also given another script written by Walon Green and Roy N. Sickner that played more into his sensibilities. The story was about a group of aging outlaws in the early 20th Century who robbed a bank in Texas and fled to Mexico where they’re forced to work for a corrupt Mexican general as they also contend with the changes in the modern world. Peckinpah would do re-writes on the script with Green as it would play into Peckinpah’s own disdain towards modern society as well as seeing what was happening around the world and in cinema with the recent release of Bonnie and Clyde which was notorious for its graphic violence. By late 1967 as Peckinpah was doing more re-writes and pre-production with the support of Feldman who would produce the film.

For the cast, Peckinpah called in some of his regulars in Warren Oates and Ben Johnson in key parts along with L.Q. Jones and Strother Martin in small parts. For other actors to join Oates and Johnson in big leading roles, Peckinpah wanted some big names as he was able to get Lee Marvin on board only to lose him when he was offered more money to star in Paint Your Wagon. Peckinpah was able to get Ernest Borgnine, William Holden, and stage actor Jaime Sanchez in the key roles with Robert Ryan and Edmond O’Brien in prominent supporting parts. Along with several parts for prominent Mexican actors like Emilio Fernandez and Alfonso Arau, the film would be largely shot in Mexico as it was definitely the ideal place that Peckinpah wanted for the film to be set as he and cinematographer Lucien Ballard also wanted to expand the visual canvas for the film.

One of the things Peckinpah wanted to do in shooting many of the scenes was to shoot it from multiple angles to get a sense of the chaos that the men are dealing with not just in Mexico but also in the emergence of the modern world. Especially with the film’s violent sequences where Peckinpah wanted as it was quite extravagant but also played into a sense of nihilism that reflected man’s view of the modern world which would relate to what is happening around the late 1960s. Helping Peckinpah with collecting all of the footage that he had shot was editor Lou Lombardo whom Peckinpah met during the editing of Noon Wine. Lombardo would create a style of editing would become a trademark of Peckinpah’s visuals which would show the violence in slow-motion. That presentation of slow-motion violence was quite disconcerting for the newly-created ratings board of the Motion Picture Association of America who would give the film the dreaded X rating. Peckinpah agreed to do some trimming to give the film its R rating so it would be seen by a wide audience while he would maintain his print of his uncut version of the film.

When the film made its premiere in June of 1969, the film divided critics as some were aghast over its violent content yet there were those who praised the film as something that was original and new. The film grossed more than $11 million against its $6 million budget which was good for Warner Brothers as the film received two Oscar nominations for Best Original Screenplay and for Jerry Fielding’s score. In 1995, the film was restored to include the ten minutes of footage that was cut out from its original theatrical release as Warner Brothers submitted the film again two years earlier to the MPAA where it received the newly-created NC-17 rating showing that the film still had the power to shock. The film would give Peckinpah international acclaim as it would put him in line with an emergence of new filmmakers who would be part of the New Hollywood movement of the 1970s.

The Ballad of Cable Hogue

With the major success of The Wild Bunch and a degree of clout from that success, Peckinpah knew he didn’t want to repeat himself as he didn’t want to make a film that was extremely violent. Having read an original script by John Crawford and Edmund Penney which was about a prospector who finds water in the middle of the Arizona desert as he would make it a watering hole for travelers during the final years of the west. The film definitely played into Peckinpah’s themes in his disdain towards modern society as well as the fact that it is set in the West. Gathering many of his collaborators for the film as well as having Jason Robards play the lead role of its titular character with a cast that include several regulars of Peckinpah in L.Q. Jones, Strother Martin, R.G. Armstrong, and Slim Pickens. Added to the cast is Stella Stevens as the prostitute Hildy whom Cable falls for and British actor David Warner as the preacher Reverend Johnson.

The shoot in the Nevada desert was plagued with problems due to weather as the $3 million budget would escalate due to these issues. Adding to the problems of the production was Peckinpah’s increase intake in alcohol as he would fire 36 crew members on set as the executives at Warner-Seven Arts became worried where they offered Peckinpah other major projects such as Deliverance and Jeremiah Johnson where he turned both films down. The two decided to part ways following its completion though Peckinpah was able to get final cut as he was also enjoying his time working with the actors on the film as he would eventually finish over 19 days over schedule.

The film was released in May of 1970 where despite making more than $5 million worldwide with $3.5 million in the U.S., the film was considered a flop as it came and went after its initial release. The critical reception didn’t help despite another rave from Roger Ebert as the film was largely ignored yet the film would later get a critical re-evaluation as some see it as one of Peckinpah’s more underrated films. Peckinpah himself would see the film as one of his favorites as it proved that there was more to him than making violent pictures.

Straw Dogs

Having burned bridges with Warner Brothers and Hollywood reluctant to work with him, Peckinpah went to Britain where he was lauded there as producer Daniel Melnick gave him a copy of Gordon M. Williams’ novel The Siege of Trencher’s Farm which is about an American professor who moves to small town in England with his family as they would be terrorized by locals over culture clash and such. Roman Polanski was offered the chance to make an adaptation of the film but was unavailable as Melnick got the rights to make the book into a film as Peckinpah wrote the script with David Zelag Goldman as they made some changes from the book and updated to be set in the 20th Century. The film wouldn’t just play into the world of culture shock but also what drives a man to go from being timid and civilized and then go into a rage to protect his family.

With Melnick’s help, Peckinpah was able to get Dustin Hoffman to star in the film while David Warner played the role of a local mentally-handicapped man in Henry Niles as he would be un-credited due to contractual reasons. Still, Warner said yes to the role as a favor for Peckinpah while the cast would include Susan George as Hoffman’s wife and Peter Vaughan as a local drunkard who is suspicious of Hoffman’s character. Since Lucien Ballard was unable to take part of the production, Peckinpah got the services of Dutch cinematographer John Coquillon to shoot the film as he would become a new recurring collaborator for Peckinpah. The film would be shot in small towns in England near it seaside locations as the film wouldn’t just be a study of man driven to the edge. It would also explore things that would drive a man to the edge as he would later learn that his wife was raped by a former lover from the town.

The film premiered in November of 1971 in the U.K. that was followed by a U.S. release a month later as the film proved to be controversial. While it was a commercial success, the film divided critics upon its initial release not just due to the rape scene but also for its violence. While the film would be re-cut trimming some of its graphic content, the film remained controversial in a period that saw an increase in sex and violence in films. Especially in Britain as it would ban the film 1984 for some time until 2002 where it was released on home video in its un-edited release. The film’s commercial success and controversy didn’t just give Peckinpah some clout outside of Hollywood but also made him a much more infamous figure.

Junior Bonner

Having allowed himself to be able to make films independently by his name alone, Peckinpah decided to make another non-violent film set in the West. He would return to the U.S. with a script by Jeb Rosebrook about a rodeo cowboy returning home in the hopes of having one more success in the rodeo circuit as well as make amends with his estranged family. The story played into not just Peckinpah’s disdain towards modern society and what the American West is becoming but also the idea of man trying to hold on to some old ideals of honor and duty during a time of capitalism. While Peckinpah’s name was attractive enough for the project, he knew he needed a big name to star in the film as Steve McQueen read the script and accepted the lead role of the titular character as it was something different from the usual films he was in.

The cast would also Peckinpah regular Ben Johnson as rodeo owner as well as Joe Don Baker as Bonner’s brother, Robert Preston as Bonner’s father, and Ida Lupino as Bonner’s mother as Peckinpah was overjoyed to work with Lupino who had given him a break during the 1950s. The film would be shot largely on location in Prescott, Arizona where Lucien Ballard returned to work with Peckinpah for the project. Despite Peckinpah’s struggle with alcoholism, the production was quite smooth as Peckinpah brought in locals to be in the film to create something that was authentic. Especially as the setting felt right into what Peckinpah wanted to tell as he sees this struggle of old values vs. new values. The film was released in August of 1972 where despite good reviews, the film didn’t do well in the box office falling very short to recoup its $3.2 million budget. The film’s commercial disappointment was surprising due to McQueen’s status as a major star while Peckinpah felt that the film’s lack of heavy violence contributed to its poor commercial take. Still, the film would largely be seen as one of Peckinpah’s overlooked gems in the coming years.

The Getaway

In a need to get himself back on track commercially, Peckinpah was approached by Steve McQueen on helming a project that is based on a novel by Jim Thompson. It was about a married couple who go on the run after killing a corrupt businessman who had given them a job to steal money from a rival bank. Peckinpah agreed to do the project and to work with McQueen again even though McQueen was the one in charge of the production that would include a script from an up-and-coming filmmaker in Walter Hill. While Peckinpah was able to get a few of his collaborators including cinematographer Lucien Ballard as well as Ben Johnson in the role of the antagonist Jack Benyon as well as small roles for Slim Pickens and a new recurring collaborator in Bo Hopkins. McQueen and his producers were able to secure one of the biggest movie stars at the time in Ali MacGraw as the female lead.

With a cast that would also include Sally Struthers, Al Letteri, and Richard Bright, the shooting would begin in February of 1972 through various locations in Texas including San Antonio and El Paso. The production was troubled not just by weather or budget but rather personal reasons as Peckinpah’s consumption of alcohol which had increased as he struggled to be sober. Tension between him and McQueen didn’t help matters as they would often argue throughout the production. Adding to the turmoil of the film was the fact that McQueen was having an affair with MacGraw as she was married to the Paramount studio executive Robert Evans as it would later become public. During filming in El Paso in April, Peckinpah sneaked into the Mexican border to marry Joie Gould whom he met in Britain during the making of Straw Dogs as she would be Peckinpah’s third wife.

After shooting was finished for the summer, Peckinpah was forced to deal with the fact that he didn’t have final cut though he was still involved in the editing of the film. Yet, his marriage to Gould only last four months as they split leaving Peckinpah devastated and increased his intake of alcohol. Peckinpah called in his longtime collaborator Jerry Fielding to do the score but following some test screenings for the film. Fielding’s score was removed and replaced by the music of Quincy Jones much to Peckinpah’s dismay as he took a full-page ad to Variety to express what McQueen had done as well as give thanks to Fielding for his work. The film made its premiere in December of 1972 where it was a major critical and box office hit. The film would be Peckinpah’s most commercially successful film of his career making more $36 million against its $3 million budget.

Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid

Despite the commercial success and clout he received for The Getaway, Peckinpah wasn’t sure about working with major studios again until actor/friend James Coburn heard about a project MGM wanted to make about Billy the Kid and his killer Pat Garrett. Peckinpah was intrigued by the project as he got a copy of Rudy Wurlitzer’s screenplay as it was a film that was supposed to be helmed by Monte Hellman but he wasn’t a big name. Peckinpah however, was a name with clout as Coburn was able to use his own power to get Peckinpah the job with Coburn playing the role of Pat Garrett. For the role of Billy the Kid, Peckinpah originally wanted Bo Hopkins but he wasn’t a major name as he would go for someone completely different by choosing country music star Kris Kristofferson to play the role of Billy the Kid. Peckinpah would do re-writes on the script to express his own view of the West dying in favor of greed as he sees both Garrett and the Kid as men who are both struggling with the emergence of this new world that they don’t want to be a part of.

The film’s ensemble cast would be the biggest as it would include Jason Robards in a cameo role as New Mexico governor Lew Wallace as well as a famed collection of renowned Western character actors in Slim Pickens, Chill Wills, Katy Jurado, Jack Elam, Barry Sullivan, R.G. Armstrong, Paul Fix, and Elisha Cook Jr. as well as roles for actors such as Harry Dean Stanton, Charles Martin Smith, Luke Askew, and some of Peckinpah’s regulars in Emilio Fernandez, L.Q. Jones, and Richard Bright. With Kristofferson already on board, the musician brought in one of his friends in Bob Dylan to the set as Peckinpah admittedly hadn’t heard of Dylan or his music but gave Dylan the chance to not only play a small role in the film but also do the music. Just as Peckinpah was ready to start shooting with cinematographer John Coquillon, problems began to emerge as Peckinpah found himself dealing with MGM studio president James Aubrey.

The numerous clashes with Aubrey would take a toll on Peckinpah during the shoot as it would force the production to relocate to Durango, Mexico while equipment would break down as well as crew members being struck with the flu. The film which was initially budgeted at $3 million would escalate as the shooting schedule was behind leading to numerous re-shoots and other issues as it increased through Peckinpah’s alcoholism. When shooting was completed in early 1973 with plans for a May release which Peckinpah felt was not long enough to do work. The post-production battle between Peckinpah and the studio became even more troublesome as the filmmaker was now gaining infamy for his reputation as being unreliable. Just before the film’s release, Peckinpah and his editors were able to complete a 122-minute preview version for a number of critics along with filmmaker Martin Scorsese who attended the screening as it was very well-received. Unfortunately, MGM wasn’t impressed as they locked Peckinpah out of the editing room to create cut of 106-minutes for its theatrical release.

The film’s theatrical release in May of 1973 did do well commercially making $11 million against its $4.7 million budget but MGM felt it wasn‘t good enough while the critical reaction was poor. Some of the reviews mentioned the preview cut that some of them had seen as they felt Peckinpah was treated unfairly by MGM for what had happened. Rumblings about the 122-minute cut would be heard for many years as it was finally shown on home video in 1988 through Turner Home Entertainment as it was got rave reviews. In 2005, the film was once again released in a special edition version running at 115 minutes that featured elements of the theatrical version, the preview version, and footage that never made it to the final cut based on Peckinpah’s notes for the film. While that version did get good reviews, many felt that the film in its preview version is one of the definitive westerns ever made.

Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia

Frustrated with the way he was treated by MGM over his last film, Peckinpah decides to make one more western but it would be set in contemporary times as he picked up an old script he wrote with friend Frank Kowalski during the production of The Ballad of Cable Hogue. The film would be about a former army officer who is tasked to find the head of a man who had impregnated a crime boss’ daughter where he encounters a load of trouble while collecting the bounty. Peckinpah would rewrite the script with Gordon Dawson as he was able to contact producer Martin Baum who read part of the script and was able to get funding from United Artists to get the film made with Peckinpah having complete control. For the lead role of Bennie, Peckinpah called in Warren Oates to star in the film as it would be a rare leading role for the character actor. Peckinpah regulars Kris Kristofferson and Emilio Fernandez would appear in the film with the latter playing the crime boss.

The cast would include Gig Young, Helmut Dantine, and Isela Vega as it would be shot largely in Mexico including Mexico City as Peckinpah would work with a largely Mexican crew including cinematographer Alex Phillips Jr. as shooting began in October of 1973. Despite Peckinpah’s own struggle with alcoholism, the film would mirror Peckinpah’s own disdain towards modern society as well as capitalism. Despite working with the Mexican crew and feeling free working in the country as he was able to work well despite the hard work it took. Peckinpah did become more of a pariah in Hollywood when he made some comments for Variety about labor as it upset some union groups in Hollywood. Peckinpah apologized for the comments as he was able to finish the shoot before the Christmas holidays and bought out a local bar with the producers for a surprise party for the crew. The post-production would be less hectic than the chaos Peckinpah endured in the last film as he and composer Jerry Fielding were able to take the time to create a soundtrack that played into the locations set in the film.

The film made its premiere in late August of 1974 as it was a major flop in the box office failing to recoup its modest $1.5 million budget while the critical response was savage with many upset over its nihilistic violence and story with some calling it one of the worst films ever made. However, there were a few that defended the film such as Roger Ebert who thought it was a masterpiece and would still maintain his opinion on the film in the coming years. While Peckinpah was proud of the film, he would be unable to see the critical re-evaluation the film would later receive as many felt it was misunderstood in its initial release as the film would also gain a cult following through rare showings on television as screenings for the film became an event in later years including a presentation in January of 2013 in Chicago where 300 people attended the screening during a snowstorm proving its stature as one of Peckinpah’s triumphs.

The Killer Elite

With a reputation that was in need of repair and reeling from films that didn’t make any money, Peckinpah decided to try and get himself back in the good graces of Hollywood just to work. Producer Martin Baum would help Peckinpah find a script as he found one that is based on a novel by Robert Syd Hopkins that revolved around betrayal and the emergence of a new world as it played into Peckinpah’s sensibilities in his disdain for modernism. Peckinpah would read the script as it would be set in modern-day San Francisco that revolved around a spy who is betrayed by his best friend and left partially-paralyzed only to take an assignment to protect a Chinese political figure unaware of a power struggle behind the scenes for the company he works for.

Peckinpah agreed to do the film but was learned that he would be unable to do rewrites or make changes to the script as it would be frustrating. While he would get James Caan and Robert Duvall in lead roles as well as getting a few of his regulars in Bo Hopkins, Gig Young, and Helmut Dantine in the film as well as noted characters Burt Young, Mako, and Arthur Hill. The production would be a difficult one due to the leash the film’s producers and United Artist had on Peckinpah to deliver the film on time and on schedule. To cope with these setbacks, Peckinpah was unfortunately introduced to cocaine from Caan’s entourage. The cocaine use would have Peckinpah be in his trailer for much of the production leaving assistant directors to direct some scenes as his cocaine use eventually lead to an overdose and heart surgery where he would get a second pacemaker. The post-production was much easier thanks to the fact that Peckinpah was able to get filmmaker/friend Monte Hellman to do some of the editing while Jerry Fielding would do the score as it would mark the last time the two would work together.

The film was released in late December of 1975 as it wasn’t well-received by critics though it did well in the box office. Yet, the film marked the beginning of a major decline for Peckinpah as he was making films that weren’t westerns as he would be offered numerous projects that Hollywood wanted. The growing disconnect he had with what he wants and what Hollywood wants would create this very uneasy and contentious relationship for the director who was in for some troubling times.

Cross of Iron

After turning down offers to do a remake of King Kong as well as helm Superman, Peckinpah decided to do something that wasn’t a film that would be very commercial. Yet, Peckinpah’s popularity in Europe as still vital as producer Wolf C. Hartwig offered Peckinpah the chance to make a World War II movie based Willi Heinrich’s novel The Willing Flesh. With the help from British producers who wanted to see the film made, Peckinpah agreed to do the film as he was able to get Julius J. Epstein, James Hamilton, and Walter Kelley to write the script with Peckinpah doing un-credited rewrites. The would be an anti-war film in some ways told from the perspective of the Germans during the conflict at the Taman Peninsula against the Soviets. Yet, it would be more about a class conflict between a cynical sergeant and an aristocratic Prussian officer as the latter is craving the Iron Cross medal.

With the exception of cinematographer John Coquillon, Peckinpah would be forced to work with a low $6 million budget as well as an inexperienced crew of West German and British workers. Despite these setbacks, Peckinpah was able to get James Coburn to play the lead role of Sgt. Steiner as well as David Warner playing the role of Captain Kriesel while the cast would mostly be noted character actors with the exception of the renowned James Mason as Colonel Brandt and Maximilian Schell as the aristocratic Captain Stransky. The film would be shot in parts of Croatia and Slovenia when it was known as part of Yugoslavia as Peckinpah wanted to create something that was real where he was able to get real tanks and equipment from World War II for the film. While Peckinpah struggled to contain his alcoholism as well as the little money he was able to use. He did use his experience in low-budget filmmaking to get things done which help him in the long run as shooting was finished in mid-1976.

The film would make its premiere in West Germany in late January of 1977 following a British premiere less than two months later as the film was well-received in Europe and did well commercially in those countries. When it was released in the U.S. in the summer of that year, it had the unfortunate timing of being released around the time Star Wars had come out. The film sunk without a trace in the U.S. as its critical response was lukewarm with critics trashing the film over its bleak content. Yet, the film would have its champions including filmmaker Orson Welles who thought it was one of the best war films he had ever seen. Critical re-evaluation for the film would later come as it was also praised by filmmaker Quentin Tarantino who was inspired by the film into his own World War II film in 2009’s Inglourious Basterds. For those close to Peckinpah, the film was seen as the last great film that he would make.

Convoy

While trying to find his next project as he would make a cameo appearance for Monte Hellman’s 1978 western China 9, Liberty 37 starring Warren Oates, Jenny Agutter, and Fabio Testi that was co-written by one of Peckinpah’s longtime fans in future Z Channel programmer Jerry Harvey. It was around the time that the era of the blockbuster had arrived as Peckinpah decided to make a film that would appeal to the masses as he had seen Hal Needham’s Smokey and the Bandit and saw how successful it was. Peckinpah decided to do a film in the same vein as those who were closest to him were baffled into why he would do it as it didn’t fit in with the themes of his other films in its disdain towards modernism and the loss of old values. Yet, Peckinpah decided to make a film based on a popular 1975 novelty song by C.W. McCall as Peckinpah hired Bill L. Norton to write the script as it would revolve around a gang of truckers who form a convoy as they run from a corrupt sheriff through the American Southwest.

The cast would feature some of Peckinpah’s regulars in Kris Kristofferson, Burt Young, Ernest Borgnine, and Ali MacGraw in her first role since The Getaway along with Franklyn Ajaye, Madge Sinclair, and Seymour Cassel in supporting roles. The film would be shot largely in New Mexico as it would be shot in late spring as Peckinpah read Norton’s finished script and didn’t like it as he allowed his actors to improvise and ad-lib lines to create some spontaneity. The shooting proved to be struggling due to Peckinpah becoming very ill due to years of substance abuse as he asked actor/friend James Coburn to shoot some second unit and eventually some scenes while Peckinpah was in his trailer doing drugs and alcohol to cope with the turmoil of the production. It added to a lot of the troubles in the production as it would eventually be completed in September of 1977 11 days behind schedule and doubling the film’s original $6 million budget.

After submitting a rough cut of the film at nearly three-and-a-half hours to EMI Films, the studio rejected Peckinpah’s cut as they asked Garth Craven to edit the film without Peckinpah’s involvement into a one-hour and fifty-minute final cut that was released in late June of 1978. The film would gross more than $45 million making it Peckinpah’s most commercially successful film to date but the critical reception was brutal as many were baffled into why Peckinpah made a film that featured some of visual attributes be seen as parody as well as make something that was silly. The critical response as well as Peckinpah’s own failing health in his addiction to alcohol and cocaine would make him a pariah in the industry as Hollywood wanted nothing to do with him. For Peckinpah, he would be out of the job for the next few years as he would toil in his own failing health until 1981 when his old mentor Don Siegel offered him the chance to direct some second unit for what would be Siegel’s final film in 1982’s Jinxed! Despite the film’s extremely troubled production that included Siegel suffering a heart attack, Peckinpah’s work, though un-credited, for the project would give him one final chance in the industry.

The Osterman Weekend

In 1982 despite his failing health, Peckinpah was approached by producers Peter S. Davis and Walter Panzer about helming a project based on a novel by the revered spy novelist Robert Ludlum who later gain fame for writing books on the character Jason Bourne. The story revolved around the world of surveillance where a controversial TV news show host is being asked by the CIA to invite his friends for a weekend outing as they believe his friends are spies for the KGB. While studios weren’t sure about wanting Peckinpah involved, Davis and Panzer stood by him feeling the project would have some respectability which would force them to find independent funding for the film. While Peckinpah admitted to not liking Ludlum’s novel or Alan Sharp’s script which was a draft, he did take the job while helping Sharp with ideas for the script.

With the exception of cinematographer John Coquillon and actress Cassie Yates who had a small role in Convoy, Peckinpah would work entirely with a new crew and actors he had never worked with yet many of them were eager to work with the director. The ensemble would include Yates, Rutger Hauer, John Hurt, Craig T. Nelson, Dennis Hopper, Meg Foster, Chris Sarandon, Helen Shaver, and Burt Lancaster as they all forgo their regular salaries as production began in the fall of 1982 around Los Angeles. The production was surprisingly smooth and in control yet Peckinpah found himself in familiar territory with his producers over the film as the 54-day shoot ended in January of 1983 as Peckinpah was barely speaking to Davis and Panzer. By the time the film was in the editing stages as Peckinpah was able to get Don Siegel’s longtime composer Lalo Schifrin to do the music, he would eventually submit his cut of the film at 116-minutes to Davis and Panzer in May of 1983.

Unfortunately, things didn’t go well as Davis and Panzer test-screened the film to an audience as it did poorly asking Peckinpah to re-cut the film but Peckinpah refused as he also had ideas to include bits of satire into the film that he had already filmed. The result had Davis and Panzer firing Peckinpah and they would re-cut the film for a final 106-minute running time that was released in December of 1983 to lukewarm reviews as it also did poorly in the U.S. box office making only $6 million against its modest $7 million. In Europe and Britain, the film was a hit on home video as it would later be considered a cult film as some felt the film featured some of Peckinpah’s finest moments in a very flawed film.

Julian Lennon-Valotte and Too Late for Goodbyes

Having burned another bridge in Hollywood, Peckinpah was given an offer by British industry figure Martin Lewis about directing a music video for Julian Lennon for his upcoming debut album Valotte that was to be released in October of 1984. Peckinpah agreed to do the video for the emerging artist as well as doing another one as it would something simple and to the point. The videos would be immensely successful in repeated airings on MTV as it would give Lennon a nomination for Best New Artist at the MTV Video Music Awards in 1985. Sadly, the videos would be Peckinpah’s final work as plans to create a film version of Stephen King’s The Regulators with a script in the works by King whom he had befriended. On December 28, 1984, Peckinpah died of heart failure at the Murray Hotel in Livingston, Montana which he had lived for five years.

Though it’s been more than 30 years since his passing and while he remains a controversial figure in cinema. There is no question the impact that Sam Peckinpah had for cinema whether it’s Hollywood filmmaking taking his style of multiple camera angles and slow-motion for elaborate action scenes to filmmakers such as Quentin Tarantino, Ben Wheatley, Robert Rodriguez, and Edgar Wright citing his films as major influences in their work. Peckinpah’s influence in cinema is immense in not just the way men deal with the modern world and changes that don’t suit their old-school values as his films have more relevance today in this ever-increasing world where humanity has become sucked in by technology. After all, if there is anyone that can be called a master of “fuck-you” cinema. It’s Sam Peckinpah.

© thevoid99 2016

Labels:

sam peckinpah,

the auteurs

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

4 comments:

What a tremendous piece. Peckinpah was definitely an amazing talent but sometimes it can be easy to forget just how the strength of his career. Anxious to dive back into this article again. Good stuff.

@keith71_98-Thank you. I hope you check out some of his films as the man was a master and certainly was someone that had a lot of balls.

This was great, so much depth - and I had no idea about the music videos. It shouldn't, but I'm always surprised not by who got their start in music videos, but who does them even after success.

@assholeswatchingmovies.com-William Friedkin directed Laura Branigan's "Self Control" back in 1985. Some did it just for work and such and it was good so it shouldn't be a total surprise. I think it was surprising for someone like Peckinpah towards the end of his life but I'm sure he saw something in Julian Lennon and just did those videos.

Post a Comment